Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1828-1882)

The son of an Italian writer and political refugee, Dante Gabriel Rossetti was brilliantly gifted as a poet as well as a painter. He was a dominant and charismatic personality, and at the age of 20 was the driving force behind the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, the secret society that aimed to reform British art. Despising convention, Rossetti shunned the official art world, preferring to sell his paintings to private collectors.

Rossetti's favorite subject was beautiful women - for the last 20 years of his life, he painted little else. Handsome, charming, and successful, he was an intensely attractive man, but his love life was strained. His wife died within two years of their marriage, and he then idolized the wife of his friend William Morris. In his last years, he became an eccentric recluse fighting drugs and alcohol and died paralyzed at the age of 53.

The artist at 19:

This self-portrait shows Rossetti in 1847, the year before he established the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. With his long hair, brooding eyes, and passionate manner, Rossetti was a striking figure, even as a young man.

An Italian father:

Gabriele Rossetti, poet, scholar, and political refugee, arrived in England, via Malta, in 1824. His son - named after Dante Alighieri, the great Italian poet - inherited Gabriele's love of literature, and became a poet as well as a painter.

Rossetti's London :

Although Rossetti was three-quarters Italian, he never visited his parents' homeland. Apart from minor trips abroad, and periods spent at Kelmscott Manor in Oxfordshire, he lived virtually all of his life in London.

THE ARTIST'S LIFE

The Passionate Victorian

The son of an exiled Italian, Rossetti never submitted to social conventions. After shocking the artistic establishment, he lived apparently 'in sin', and died an eccentric recluse.

Dante Gabriel Rossetti was born in London on 12 May 1828 and grew up in one of the most remarkable families in Victorian England. His father, Gabriele Pasquale Giuseppe Rossetti, was an Italian poet and scholar who had fled his native country after being sentenced to death for his involvement in a revolutionary secret society. Gabriele settled in England in 1824 and two years later married Frances Mary Lavinia Polidori, a onetime governess, and teacher who was the daughter of another Italian exile and an English mother.

Dante Gabriel was the second of four children, all born within four years of each other, and all intellectually gifted. They were brought up to speak Italian as well as English, and Maria, the eldest, became a scholarly authority on the Italian language. Christina won fame as one of the finest poets of her period, while William Michael established himself as one of the leading art critics of the day. Yet their mother later made the illuminating comment that it might have been better to have a little less intellect in the family so as to allow for a little more common sense.

Gabriele earned his living by teaching Italian, and in 1831 became a Professor of Italian at King's College in London. In spite of its impressive title, the post was not well paid, and the family home on Charlotte Street (now Hallam Street) near Regent's Park was fairly humble. However, the job meant that he could have his sons taught for free or at reduced fees at King's College School. So Dante Gabriel and William Michael both had a good education, which included drawing lessons.

Rebel at the Academy:

Rossetti studied at the Royal Academy but rejected both its academic teaching and the lifeless' paintings that hung there. Instead of exhibiting at the RA, he preferred to show his paintings at the Free Exhibition sited near Hyde Park.

AN INDOLENT PUPIL

Dante Gabriel's childhood love of drawing was so intense that his brother later observed that it was always understood that he would become a painter. When he left King's College School at the age of 14, Dante Gabriel was sent to Sass's Art School, a drawing academy that was the normal stepping stone to the Royal Academy Schools, to which he progressed in 1845. His three-year period at Sass's was longer than usual, because he hated having to submit to the academic discipline of drawing from antique sculpture, and was an indolent pupil: 'As soon as a thing is imposed on me as an obligation, my aptitude for doing it is gone; what I ought to do is what I can't do.'

The young student Rossetti was striking figure. He was remarkably handsome, with beautiful blue-grey eyes and flowing locks of auburn hair, and he already possessed a personal magnetism that made him the centre of attraction in any company. As his brother recalled, 'Apart from his mental gifts, the quality most innate in him appears to have been dominance. He was imperative, vehement, at times angrily passionate; but his anger was a sudden and passing impulse, and to sulk or bear a grudge was not in him at all.'

LETTER TO A PAINTER

But Rossetti was no happier with the routine at the Royal Academy than he had been with that at Sass's and in March 1848 he wrote to a painter he admired, Ford Madox Brown (then aged 26), asking him to take him on as his pupil. The letter was so gushingly effusive that Brown, who had a prickly temperament, thought that it was intended sarcastically and stormed round to the Rossetti house with a cudgel. Rossetti soon convinced him of his sincerity and Brown agreed to accept him as an informal pupil, while he was still officially attached to the Royal Academy.

Although Rossetti was impressed by the seriousness and literary inspiration of Brown's paintings, he was dismayed when Brown tried to teach him the same traditional, academic skills that he had already rejected. He soon abandoned the idea of an apprenticeship with Brown, but they remained lifelong friends.

As he approached his twentieth birthday, Rossetti was still uncertain whether he should make literature or painting his career. He sent some of his poems to Leigh Hunt, a distinguished poet, and critic, who praised them warmly, but sensibly pointed out that it was much harder to make a living as a poet than as a painter: 'If you paint as well as you write', advised Hunt, 'you may be a rich man.' Although he was overflowing with ideas, Rossetti had not yet produced any significant work as a painter, but the way forward opened up to him as his friendship grew with two fellow students at the Royal Academy: William Holman Hunt and John Everett Millais.

The Lovely Lizzie

Rossetti met his future wife Elizabeth Siddal in about 1850. 'A most beautiful creature - tall, finely framed, with a lofty neck... and a lavish heavy wealth of coppery-golden hair', she had been introduced to him by the painter Walter Deverell, who had spotted her in a milliner's shop. Her soulful good looks made her the perfect model for the Pre-Raphaelites, but she also became a painter and poet in her own right. She died of an overdose of laudanum in 1862, not quite two years after marrying Rossetti.

A melancholy beauty:

Rossetti made this tender drawing of his 'Ideal Beloved' Lizzie in 1855, five years before their eventual marriage.

Model for Shakespeare:

Lizzie Siddal's delicate features appear in many Pre-Raphaelite paintings. This detail of Holman Hunt's illustration from Two Gentlemen of Verona shows her in the guise of the heroine Sylvia.

THE PRE-RAPHAELITE BROTHERHOOD

These three young men were widely different in temperament and talents, but they shared a sense of dismay at what they considered the moribund state of British art. In order to express their rejection of the lifeless artistic conventions which they saw as stemming from the 16th-century master Raphael, Rossetti, Millais, and Hunt decided to call themselves ‘Pre-Raphaelites'. They were joined by Rossetti's brother and three other friends, and in 1848 the seven young men formed a secret society they called the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood.

Rossetti's first major oil painting, The Girlhood of Mary Virgin, was the first painting exhibited bearing the Brotherhood's initials PRB. It was warmly praised and was bought by the Dowager Marchioness of Bath for 80 guineas. Rossetti's career as a painter seemed to be taking off, but in the following year, he was brought sharply down to earth. When the meaning of the initials PRB leaked out, he and his associates were savagely attacked in the press and denounced as upstarts who had besmirched the name of Raphael - who was almost universally regarded as the greatest painter who had ever lived.

Rossetti was so upset by the criticism that he vowed never again to exhibit in public. He rarely broke the vow, and in the decade 1850-60, he virtually abandoned oils and worked on small watercolors. The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood was breaking up and Rossetti, who had for a time shared a studio with Hunt, found rooms of his own at 14 Chatham Place, near Blackfriars Bridge. Although he was not exhibiting, his watercolors began to sell well, often to contacts of the famous art critic John Ruskin, whom he met in 1854.

Ruskin and Rossetti:

In 1854, the art critic John Ruskin wrote to Rossetti, expressing admiration for his work. It was the start of a stormy but long-lasting friendship, in which Ruskin adopted the roles of both champion and mentor.

Tudor House:

After Lizzie's tragic death, Rossetti moved from Blackfriars to the grand 'Tudor House' in Cheyne Walk, Chelsea. For a short while, he shared his home with the novelist George Meredith and the poet Algernon Swinburne, until the latter's childish, and often drunken, behavior proved too much to bear.

Ruskin was one of several new friends who had a great impact on Rossetti's life in the 1850s. In 1850 (or perhaps late 1849) he met his future wife Elizabeth Siddal, the first of the beautiful women ('stunners', as he called them) who were to haunt his imagination and provide him with unending inspiration for his painting. The red-haired Lizzie was discovered by Walter Deverell, a painter friend of Rossetti when she was working in a milliner's shop in Leicester Square.

Lizzie may well have been in love with the handsome and charming Deverell, who died aged 26 in 1854. But although she became very sickly after his death, a deep mutual attraction gradually grew between her and Rossetti.

From an outside observer's viewpoint, it probably seemed that they lived in sin' for several years before their eventual marriage in 1860. But their relationship was unusual by any standards and often strained. Though Rossetti became more and more obsessed with Lizzie, he saw her as an 'ideal beloved' - who should be worshipped, but not touched. Like many Victorian men, Rossetti divided women into two classes - angels and whores - and sexual intimacy with Lizzie would have sent her tumbling from the pedestal on which he had placed her.

A MISTRESS FOR LIFE

So he looked elsewhere to relieve his sexual tensions. His most long-lasting affair was with a woman called Sarah Cox (later known as Fanny Cornforth), whom he first met in about 1858. According to one account, he picked her up in the Strand, where she had attracted his attention in a none-too-subtle fashion by cracking nuts between her teeth and throwing the shells at him. Buxom, healthy and with an earthy sense of humor, was the complete opposite of the fragile Lizzie. And though the relationship broke up after Lizzie and Rossetti's marriage, it was later resumed and continued almost until his death.

In 1856, Rossetti formed a friendship with two undergraduates at Oxford, William Morris, and Edward Burne-Jones. The following year he helped them and several other young artists to decorate the debating chamber of the Oxford Union with scenes from Arthurian legend. And in the 1860s Rossetti and Burne-Jones were two of the leading artists to work for Morris's new firm of 'fine art workmen'.

In May 1861, 12 months after their marriage, Lizzie gave birth to a still-born daughter. By the following spring she, too, was dead: her constant ill health and depression led her to rely on laudanum, an addictive medicine containing opium, and she died of an overdose. Rossetti was devastated. Indeed, he was so grief-stricken that he had the only complete manuscript of his poems buried with her. (He had them exhumed in 1869 and published in 1870.)

Fanny Cornforth:

Rossetti's The Blue Bower features his mistress and model Fanny Cornforth. While Lizzie Siddal was his ideal love, Rossetti enjoyed a more physical relationship with Fanny -- a forthright cockney woman, some four years his senior.

A Teacher and Friend

Having studied art throughout Europe, Ford Madox Brown was struggling to establish himself as a painter of early historical subjects when Rossetti wrote to him fervently requesting painting lessons. Their pupil-teacher relationship only lasted a few weeks, but they remained affectionate friends. Though Brown was sympathetic to the aims of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, he never joined it. In 1861, however, he joined Rossetti as a founder member of William Morris's decorating company.

Ford Madox Brown:

Only seven years older than Rossetti, Brown was already a widower when they met in 1848, and renowned for his 'peppery' temperament. However, he generously agreed to give his young admirer free tuition.

The Last of England:

This picture was inspired by the emigration of the Pre-Raphaelite artist Thomas Woolner. The fluttering ribbons took Brown four weeks to paint.

THE MOVE TO CHELSEA

In October 1862, the widowed Rossetti moved from Blackfriars to the grand Tudor House in Chelsea's Cheyne Walk, where Fanny Cornforth reappeared in his life, as his model, mistress, and housekeeper. His paintings of her were more richly sensuous than those of the ethereal Lizzie, and they sold well. Rossetti was a hard businessman in his relationships with picture dealers, and in the 1860s his income rose to £3,000 per year.

When Rossetti discovered another voluptuous model, Alexa Wilding, in the street, he could easily afford to pay her an annual retainer. She sat for many of his most splendid paintings, but the fact that more than any other dominates Rossetti's later work is that of William Morris's wife, Jane. Rossetti had met Janey in 1857, two years before she married Morris. As Lizzie, she was tall and stunningly attractive, and like Lizzie, she became a permanent semi-invalid. Fanny Cornforth (and others) might satisfy Rossetti's physical needs, but Janey fulfilled his desire for ideal, mystical love.

In 1872, Rossetti (now wealthy enough to - employ assistants) suffered a physical collapse. He was drinking heavily and also taking the anesthetic drug chloral in an attempt to stave off chronic insomnia. Although he recovered, most of the last 10 years of his life were spent as a virtual recluse in Chelsea. Alcohol and drugs took a heavy toll, and often his hands shook so much that he was unable to work.

Rossetti had changed greatly in appearance since his days as a beautiful youth. He became stout, and his darkly-ringed eyes gave him a rather saturnine look. But he could still be a compelling figure and a brilliant conversationalist. He also gained a reputation as an eccentric. His house was full of antiques and all manner of bric-à-brac and in the garden, he kept a menagerie of exotic animals including armadillos, raccoons, and peacocks. Most of the animals were bought to satisfy passing whims and they were often neglected, but he had a touching affection for a pet wombat and wrote a poem lamenting its death.

Janey and the wombat:

William Morris's beautiful, dark-haired wife became the object of Rossetti's adoration after Lizzie's death. In this drawing of Janey, the artist shows her with the pet wombat from his garden menagerie.

The Rossetti family:

The author Lewis Carroll took this photograph of the Rossetti family in the Tudor House garden in 1863. The artist and his brother William Michael stand on either side of their sister Christina and their mother. The artist's father had died nine years before.

Ill, depressed, and old before his time, Rossetti rarely left the house in his final years, except to visit his old friend Madox Brown or his mother and his sister, Christina. And in December 1881, the ailing artist had a stroke that left him partially paralyzed in the left arm and leg. He ended his long relationship with Fanny - the cockney 'Helephant whom his friends had never accepted - and in February 1882 went to convalesce at Birchington-on-Sea, near Margate in Kent.

Rossetti died there aged 53, on 9 April - Easter Sunday. He had left instructions that he was not to be buried beside Lizzie in Highgate Cemetery (perhaps because of feelings of guilt at having desecrated her grave), and was buried in the churchyard at Birchington.

A Victorian Interior:

This watercolor painted the year of Rossetti's death, shows him at home with his friend and legal adviser Theodore Watts-Dunton, amid the collection of antiques and bric-à-brac in the Tudor House. It was painted by Rossetti's assistant, H.T. Dunn.

Sea-side burial:

Rossetti died, aged 53, while convalescing from a stroke at Birchington-on-sea in Kent, and was buried in the churchyard there. On his tombstone, designed by Ford Madox Brown, an eloquent epitaph records that he was 'honored among painters as a painter, and among poets as a poet'.

THE ARTIST AT WORK

A Romantic Dreamworld

Rossetti thought of himself as a poet in paint rather than a craftsman. Medieval romance and beautiful women were his favorite subjects, and he painted both with original techniques.

With his strong personality and scant res the conventions of the day. Dante Gabriel became one of the most individual artists of the 19th century. Even when he was a member Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, his attitude and technical methods were clearly different from those of his colleagues, who in theory all subscribed to the same ideals.

Rossetti was not a natural craftsman like Millais, to whom painting came almost as easily as breathing, nor did he have the patience of Holman Hunt, whose work owes more to dedication than to inspiration. The young Rossetti, with his lack of thorough technical training, was in the position of a musician who has great melodies running through his head but has not yet even mastered the scales.

FLAWED MASTERPIECES

His first two major oil paintings, The Girlhood of Mary Virgin and The Annunciation, are ambitious and original works, but they clearly show his limitations in draughtsmanship and perspective. In The Annunciation, for example, there is awkwardness in the tilted effect of the bed on which the Virgin sits and in the positioning of the angel's feet, but it is typical of Rossetti that the spirit of the work overcomes any technical deficiencies. The daring, almost all-white color scheme and the exquisite expression of the Virgin convey a feeling of elevated purity.

Although Rossetti shared the PRB practice of using family and friends as models for his paintings, he was never interested in the minute particularity of detail that was such a feature of the work of his colleagues.

The plain white walls and floor in The Annunciation required no elaborate archaeological research and reconstruction, nor the expenditure of a whole day on a few square inches of paint. Rossetti tended to avoid complex backgrounds and he had a positive distaste for landscape, a feature to which Millais, in particular, devoted so much loving attention.

Rossetti also differed from the other PreRaphaelites in the large part that watercolor played in his work. It was his favorite medium in the 1850s and he developed a highly original technique, which he applied mainly to su from medieval romance. Watercolour reached its highest development in England late 18th and early 19th centuries, but ko technique was very different from the method of applying transparent washes to create what was in effect a tinted draw Rossetti applied the paint vigorously, even roughly, producing sparkling, jewel-like effects entirely appropriate to the heraldic trappings he so often portrayed, as in The Wedding of St George and Princess Sabra.

Found (1853):

Rossetti's only attempt at a modern-day morality subject. This elaborate drawing shows a countryman on his way to market recognizing his former beloved, who has now become a prostitute in the city.

The Blue Closet (1857):

This colorful watercolor is typical of Rossetti's work in many ways: in its medieval setting, its musical theme (the meaning of which is obscure), and its bevy of languidly beautiful women.

The Preparation for the Passover in the Holy Family (1855):

Rossetti's highly original water color technique is clearly demonstrated in this unfinished picture. Mary's blue robe shows how Rossetti used very dry pigment; he also scraped through it with the 'wrong end of the brush for texture.

Sir Galahad (1857):

Rossetti made several fine illustrations for the Moxon edition of Tennyson's poems, to which Millais and Hunt also contributed.

Paolo and Francesca da Rimini (1855):

Although often indolent, Rossetti could work quickly when necessary. This watercolour was painted to help Lizzie Siddal, who had run out of money travelling in France. Madox Brown wrote that Rossetti 'worked day and night, finished it in a week'.

UNUSUAL TECHNIQUES

He made much less distinction than did most artists between watercolour and oils and might use techniques in one medium that would normally seem more appropriate to the other. Often his watercolours look solid and richly textured (he frequently used the paint almost dry, rather than free-flowing - rubbing and scraping at the paper), while his oils sometimes have an almost ethereal delicacy. His friend William Bell Scott (like Rossetti a poet as well as a painter) saw Rossetti at work on The Girlhood of Mary Virgin and noted that he was 'painting in oils with watercolour brushes, as thinly as in watercolour'. It is because of these technical idiosyncrasies,

that Rossetti's paintings sometimes look rough or unfinished, but they have an inner glow that is so often missing in the work of artists who achieve an effortless surface polish.

In spite of his hatred of academic discipline, Rossetti was also an outstanding draughtsman among the Pre-Raphaelites. He used drawing not only as a preparation for painting but as a means of expression in its own right, and in the 1850s he was obsessive in the way he drew Lizzie Siddal (or 'Guggums' as he called her) again and again. Madox Brown wrote after a visit to Rossetti in 1855: Rossetti showed me a drawer full of "Guggums"; God knows how many. It is like a monomania with him.

Although he often became totally immersed in certain themes, Rossetti at times showed considerable versatility. His experiments with wall painting at the Oxford Union in 1857 were a dismal failure because he was cavalierly amateurish in technique, but his association with William Morris brought out his talent as a designer of stained glass. And as might be expected of an artist as deeply immersed in literature as Rossetti, he was a brilliant book illustrator, although he au comparatively little work in this field. His illustrations of his sister's poems are among the most charming works.

For the last two decades of his career (he stopped working in 1878, four years before his death), Rossetti concentrated almost exclusively on paintings of beautiful, sensuous women. Fanny Cornforth was his favorite model for a while and then Janey Morris. With her pouting lips, smoldering eyes, and cascades of curls, Janey became in Rossetti's images of her one of the archetypal personifications of the femme fatale.

COMPARISONS

The Femme Fatale

The theme of the femme fatale - an irresistibly beautiful woman who brings disaster to the men she entangles - has a long tradition in the history of art. Biblical themes frequently provided the pretext for pictures in which sex appeal played a much greater part than piety. Salome is probably the most famous femme fatale in the Bible: King Herod was so smitten by her that he granted her wish for the head of John the Baptist. Judith used her charms to similar effect but for an arguably more noble purpose. She infiltrated the camp of the Assyrian enemy and killed the enemy general.

Titian (c.1490-1576) Salome:

The great Venetian painter Titian excelled in the depiction of sensuous textures. Here the ghastly severed head contrasts strongly with Salome's voluptuous flesh.

Gustav Klimt (18621918) Judith:

Klimt was one of the supreme exponents of the 'decadence' which was so fashionable around 1900. His Judith looks completely secular - and very seductive.

DIVINELY BEAUTIFUL FORMS

Often these paintings have titles in Italian or Latin, but although they may evoke mythological or literary references they have no story-telling element. Rossetti's friend and pupil Edward Burne-Jones gave a description of his own ideas on a painting that could well be applied to Rossetti's late work: 'I mean by a picture a beautiful romantic dream, of something that never was, never will be - in a light better than any that ever shone - in a land, no one can define or remember, only desire - and the forms divinely beautiful.'

Rossetti's later work is uneven, partly because of his ill health, and partly because he employed assistants, but his finest paintings are among the most memorable and enduring images of the 19th century. They were immensely influential and had a whole legion of descendants in the moody, brooding femmes fatales who were so much a part of the decadent taste of the 1890s.

Proserpine(1877):

This painting is a superb example of the intensity with which Rossetti focuses on various part of the female body. his friend Theodore Watts-Dunton said that to Rossetti the eyes represented the spiritual part of the face and the mouth the sensuous part. The hands also are deeply expressive.

THE MAKING OF A MASTERPIECE

The First Anniversary of the Death of Beatrice

Angered and hurt by the abuse hurled at the Pre-Raphaelites stopped exhibiting his work in public, and in the 100 painting watercolors for private collectors. This was -and, at two feet wide, his largest - watercolor Irish businessman named Francis McCracken carefully, but his vivid reconstruction of me imaginative rather than scrupulously historical; in inspiration to northern European artists such a than to the great Italian masters. He spent ab on the painting and McCracken was so pleased £50 instead of the agreed fee of 35 guineas.

Tender companions:

The gently clasped hands of Dante's companions, who come to visit him on the anniversary of his beloved's death, are typical of the tenderness of the painting

Domestic details:

Rossetti's painting is crowded with details, some symbolic, some decorative, and others serving mainly to create a convincing picture of a medieval interior. The water ewer, basin, and towel help to evoke an air of everyday domesticity.

Inspiration from the 16th century:

This detail from a woodcut of the birth of Mary by Albrecht Durer shows Rossetti's source for his still-life detail on the left.

Friends as models:

Elizabeth Siddal posed for the woman visitor; her elderly companion was a family servant called Williams.

Symbols of mortality:

The still-life details beside the kneeling figure of Dante are symbolic references to the transience of earthly life. They include a lyre and a book, alluding to intellectual pleasures, and a skull - well-recognized as the universal symbol of death.

An early version:

Rossetti made this pen-and-ink drawing in 1848-49, five years before the water-colour.

Gallery

Rossetti was in his early twenties when he first came to prominence as a member of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. The Girlhood of Mary Virgin and The Annunciation is his key paintings of this period, serious and devout works, but captivating in their youthful ardor and freshness.

After the critical attacks on the PRB, Rossetti withdrew from the public art world d and for a decade concentrated on watercolors. The Wedding of St George and the Princess Sabra is typical both of his medieval themes and of his love for sparkling color and elaborate heraldic patterns.

Following the death of his wife, commemorated in Beata Beatrix, Rossetti devoted himself almost exclusively to paintings of beautiful women. His favorite model was Janey Morris whom Rossetti immortalized in a series of powerful images: paintings that are both grand and highly erotic. The most splendid of them all is Astarte Syriaca, the final testimony to Rossetti's lifelong love of female beauty.

The Girlhood of Mary Virgin 1849:

This was Rossetti's first important oil painting and his first public success. Modeled by Rossetti's sister and mother, it has great charm in the touching simplicity of the poses and expressions and is full of symbolic details. Rossetti wrote a sonnet explaining them: the lily in the vase next to the angel, for example, stands for

innocence.

Beata Beatrix 1864:

Rossetti painted this intensely spiritual picture as a memorial to his wife, who died in 1862. In it he expresses his love for Lizzie as being parallel to Dante's idealized love for Beatrice, whose death had left the Italian poet grief-stricken. The bird is a messenger of death, carrying a poppy - a flower that induces sleep.

Monna Vanna 1866:

One of Rossetti's most sumptuous paintings, this is a portrait of Alexa Wilding, who regularly modelled for him during this period.

The name 'Monna Vanna' occurs in the poems of both Dante and Boccaccio but has no specific connotation here. Rossetti considered this one of his finest works and he never surpassed it.

IN THE BACKGROUND

William Morris and Co.

Inspired by the romantic yearnings of Rossetti, William Morris founded a famous company. It was dedicated to the ideals of medieval craftsmanship and to 'decorative, noble, popular art'.

Rossetti is best remembered for his part in the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood and for his paintings of exotic femmes fatales, but an important part of his life was his association with William Morris (1834- 96), the finest artist-craftsman of his time. Today, Morris is most famous for his beautiful wallpaper designs, but in his own day he was renowned as a poet and social reformer, and he was one of the most energetic figures of the Victorian era. His artistic and literary output would have been E enough to occupy the lifetimes of 10 ordinary men.

When the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood was formed in 1848, Wiliam Morris was a schoolboy entering the gates of Marlborough College in Wiltshire. He first learned of the brotherhood through John Ruskin's Edinburgh Lectures, which he read while a student at Oxford in 1854, and enthusiastically narrated to his fellow undergraduate, Edward Burne-Jones (1833-98). Both Morris and Burne-Jones were immediately inspired by the idea of contemporary painters reviving medieval art and were attracted to the romantic figure of Dante Gabriel Rossetti.

The philosopher of design:

The craftsman William Morris believed that you should have nothing in your house that you do not know to be useful and believe to be beautiful.

MASTER OF MANY CRAFTS

In 1856, Morris joined Burne-Jones in London to paint under Rossetti's guidance and, in a typical fit of enthusiasm, he declared, 'I want to imitate Gabriel as much as I can'. But he was far too original and versatile a man to remain dominated for long. He mastered a whole range of crafts, including weaving, dyeing, stained glass, blockmaking, printing, and book illumination, and he had a great facility for poetry.

In every sense, Morris was a larger-than-life figure. Affectionately known to his friends as Topsy, on account of his uncontrollable mane and beard, he was the constant butt of practical jokes and frequently used to find that his companions had sewn tucks into his waistcoat overnight, knowing that he suffered from a terrible fear of getting fat. His normally jovial nature supported such jokes, but he was also given to explosive fits of rage, when he would hurl sub-standard dinners straight out of the window, break the furniture into pieces and grind forks into a frenzied knot with his teeth.

After a brief attempt to paint under Rossetti, Morris decided to set up a firm that would specialize in the design and manufacture of decorative and useful goods. Morris, Marshall, Faulkner & Co. (soon known as Morris & Co.), s came into being in April 1861, and the founder members, who each put up £1, were Rossetti, Burne-Jones, Ford Madox Brown, Charles E Faulkner (an accountant), P. P. Marshall (a surveyor), Philip Webb (an architect), and Morris.

At Oxford, Morris had been greatly influenced by Ruskin's notion that medieval art was the expression of a free and happy way of life. Morris & Co. therefore was based on the ideal of a medieval craft guild, where the craftsman designed and executed his own work, and where there was no division of labour into 'intellectual work and more degrading 'manual' work. The objects were not to be produced by machines and they were to be in a medieval style - a far cry from the tasteless, mass-produced artifacts which cluttered the typical Victorian interior.

In practice, however, much of the company's work was manufactured by outside firms and some machines had to be used for printing and weaving. Workmen had to be employed, for example, to cut wood-blocks for wallpapers, and to cut the lead for glass for stained-glass windows, although Morris supervised these operations.

The firm's prospectus issued in 1861 optimistically offered to provide wall paintings and decoration, stained glass, metal work, jewelry, sculpture, embroidery, and furniture, all ‘at the smallest possible expense', but in fact, the company relied on commissions from Webb to furnish houses, and from church architects for stained glass and for wall- and roof-decorations. Webb himself designed the furniture, much of which was painted by Rossetti, Burne-Jones, Madox Brown, and Morris. All five of the artists produced their own designs for the stained glass work which was soon to become the financial backbone of the company.

A wallpaper masterpiece:

Morris's drawing for the Chrysanthemum wallpaper (1876) shows him using motifs from nature o create a vigorous, closely-patterned design.

The early 1860s were halcyon days for the group. Evenings would be spent at Morris's 'Red House' at Bexleyheath in Kent, in a heated discussion about medieval art, or listening to Morris chanting out his 'grinds', as Rossetti nicknamed his lengthy poems. No one took any interest in the financial affairs of the company, which in its first decade was always on the verge of bankruptcy, although Warrington Taylor, who took over the accounting in 1864, tried to make Morris economize.

Oxford's medieval beauty:

When William Morris went to Oxford in 1853, he found the university town an inspiration. Together with his fellow undergraduate, Edward Burne-Jones, he discovered the beauties of Gothic art, and the medieval colleges and cloisters became their 'chief shrines'.

A bitter quarrel:

Rossetti, one of the founder members of the firm, was enraged when Morris decided to dissolve the partnership in 1875. To vent his spleen, he drew this cruel caricature of 'Topsy' Morris tumbling down to Hell.

Stained glass windows:

Morris's innovative firm, founded in 1861, specialized in the 'manufactory of all things necessary for the decoration of a house. In its first years, however, the mainstay of the company was stained glass commissions for small churches.

Queen Guenevere (1858):

William Morris's only completed oil painting is a portrait of his wife Janey, whom he adored. Melancholy and withdrawal, she was the archetypal Pre-Raphaelite beauty: the novelist Henry James described her as 'a dark silent medieval woman with her medieval toothache'.

BUSINESS BOOMS

In 1870, however, the firm started to receive more commissions, and during the next decade, it expanded rapidly as Morris threw himself into experiments with dyeing and weaving. The range of products could now include woolens, silks, chintzes, embroideries, machine-made carpets, and famous wallpapers which allowed Morris to combine his passion for nature with his feeling for pattern and color. He could be seen shuffling about in his old felt hat and a blue coat barely encompassing his widening girth, stained with indigo from top to toe. The work provided relief from the tension of his unsuccessful marriage to the beautiful Jane Burden, whom Morris idolized from a distance, but could not communicate with.

Rossetti had fallen in love with Jane, and the strains which this caused erupted in 1875 when Morris proposed that Rossetti, and the other founders who had ceased to contribute work, should be retired. Rossetti was not satisfied with the compensation offer and their friendship ended.

The firm continued to prosper for the rest of Morris's life, but as he became increasingly immersed in socialism and the theories of Karl Marx he could never quite justify its success. Morris believed that good art could not be produced by a society dedicated to profit, and wanted to produce art for the masses, but his products were too expensive for the ordinary working man. And while he railed against the aristocracy and the capitalist system, he was designing wallpaper for Queen Victoria's country seat at Balmoral and ministering to the 'swinish luxury of the rich.

Nor were Morris' own artistic tastes really suited to the masses. For example, he had a passion for collecting old, rare, and expensive illuminated manuscripts. These were the inspiration for his final concern, the setting up of the Kelmscott Press in 1891, to produce beautifully bound and printed editions of classic works, including the famous Kelmscott Chaucer. But if he could not reconcile his own ambitions with his achievements, Morris did at least have a tremendous influence on succeeding generations of designers, who adopted his ideals of functionalism combined with good design. His own wallpapers and textiles are still being produced and sold commercially today - by the firm of Sanderson & Co.

Family friends:

Morris remained lifelong friends with Burne-Jones and became devoted to his wife, Georgiana. This 1874 photograph shows the Morris and Burne-Jones families – with Janey, second from the right, in a typically sullen pose.

Woodpecker tapestry:

Morris soon mastered the arts of dyeing and weaving, and by 1880 was producing subtle and intricate tapestry designs. This tapestry was woven in 1885 on a special loom at the firm's Merton Abbey works.

The Kelmscott Chaucer:

In 1891 Morris established the Kelmscott Press, producing handprinted books with handsome bindings. His most elaborate project was the Kelmscott Chaucer (1896), with its 87 woodcut illustrations by Burne-Jones.

Kelmscott Manor, Oxfordshire:

Kelmscott Manor, Oxfordshire Morris's bedroom at Kelmscott Manor shows the beauty of his interiors. The hangings of the Elizabethan bed were embroidered by his daughter May.

William Blake ‘The Painter Poet’

-

Posted by

Umaid

- 0 comments

Warli Painting

-

Posted by

Umaid

- 0 comments

Titian ‘The Italian Renaissance’

-

Posted by

Umaid

- 0 comments

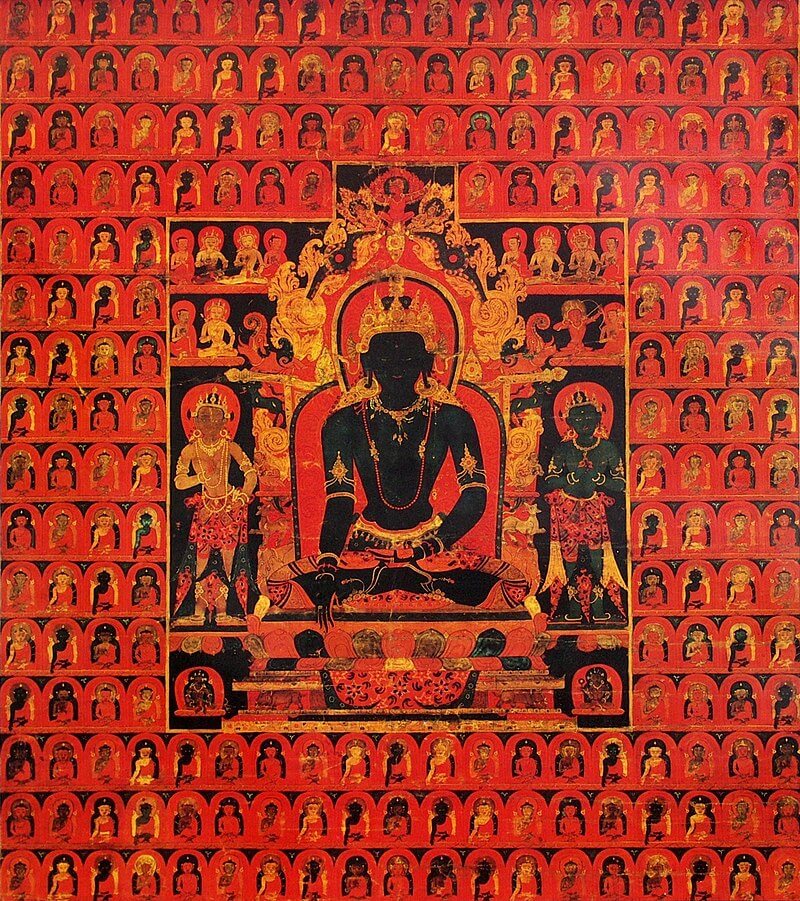

Thangka Painting Style

-

Posted by

Umaid

- 0 comments

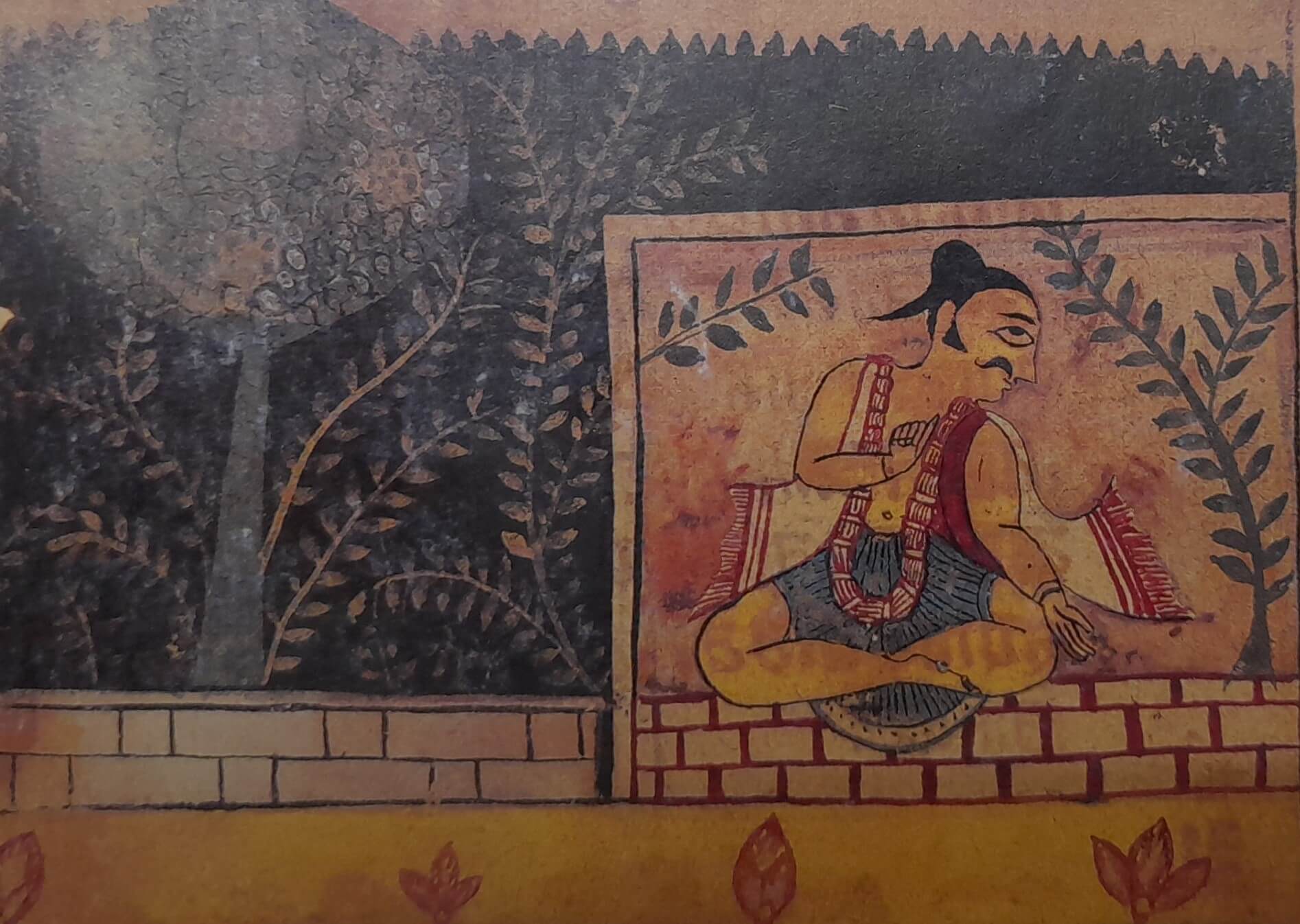

Pre- Mughal Traditions of Painting in Marwar

-

Posted by

Umaid

- 0 comments

Pieter Bruegel the Elder ‘The Draughtsman and engraver ‘

-

Posted by

Umaid

- 0 comments

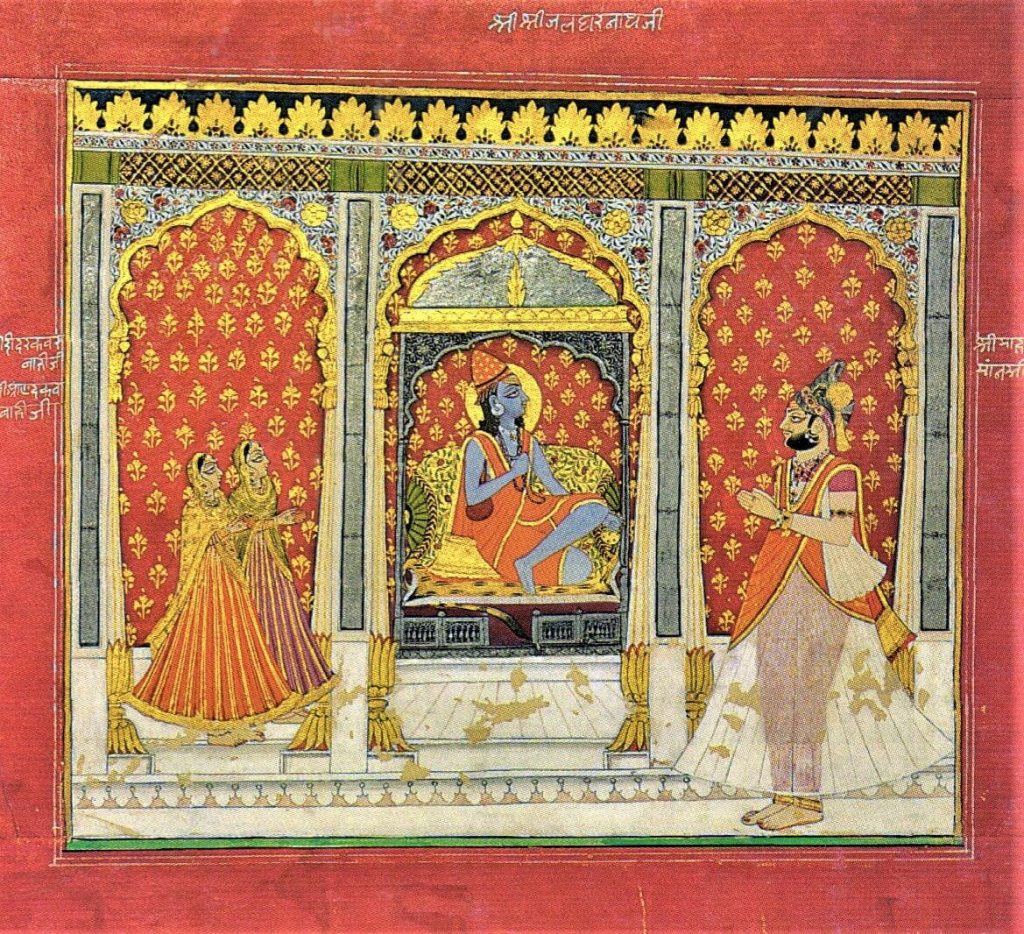

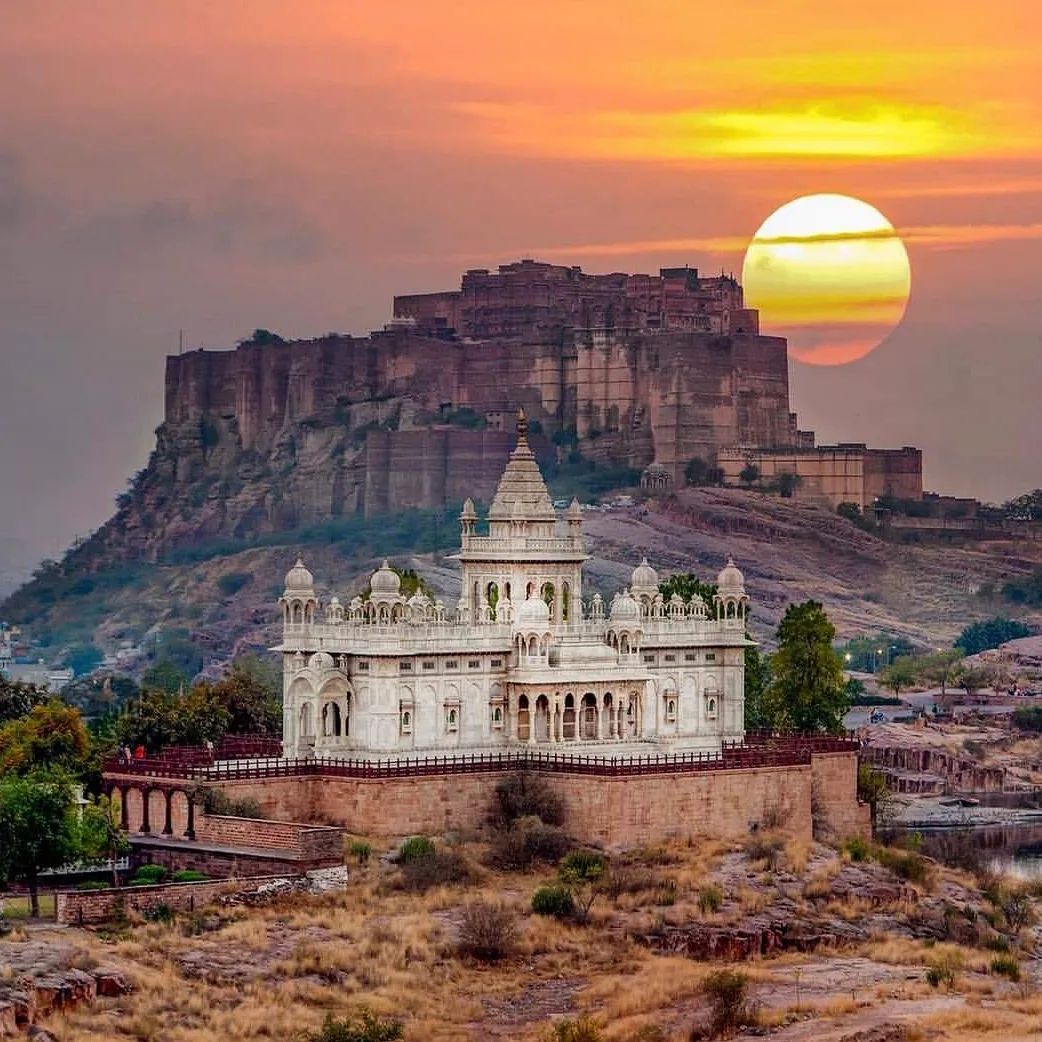

Pichwai Paintings of Rajasthan

-

Posted by

Umaid

- 0 comments

Phad Paintings of Rajasthan

-

Posted by

Umaid

- 0 comments

Paul Gauguin ‘Mysteries of Paradise’

-

Posted by

Umaid

- 0 comments