Fra Angelico (1395-1455)

Fra Angelico entered the Dominican order of friars as a young man and began his artistic career decorating manuscripts. He was portrayed in the writings of Vasari as a deeply pious man concerned not at all with the affairs of the world but devoted firstly to religion, and secondly to art. However, his work attracted the attention of secular as well as Church patrons and he traveled widely to fulfill his many commissions.

Even his early works show some appreciation of Renaissance ideas. Fra Angelico used all he knew of perspective, color, light, and shade to produce panel paintings that are among the most captivatingly beautiful and memorable works of their period. But it is on his frescoes that Fra Angelico's fame rests, for it is with these wall paintings that he proved himself part of the great Italian tradition of monumental decoration.

THE ARTIST'S LIFE

The Friar of San Marco

Though he entered a monastery while a young man, Fra Angelico was not a naïve ascetic. He was both monk and a professional artist, whose faith was enriched by the new ideals of Humanism.

No one knows exactly when Fra Angelico was born but it is known that his real name was Guido di Pietro (Guy, son of Peter) and that he came from Vicchio, a small town about 20 miles north-west of Florence.

Fra Angelico's birth date has traditionally been given as 1387, but this is based on the idea that he entered the Dominican order of friars in 1407 as recorded in a 16th-century chronicle of the order. However, a more recently discovered document shows that he was still a layman - although already a painter - in 1417. The 1407 reference is probably incorrect: he actually took his holy orders at some time between 1418 and 1421. Given that it would be normal to enter the monastery in the late teens, this suggests he was born between 1395 and 1400, the dates favored by modern scholars.

The reason for the uncertainty is that Fra Angelico lived at a time when the period of the Middle Ages was just beginning to give way to the Renaissance. In medieval society, much less attention was paid to artists. The deeds of Michelangelo or Leonardo, just a few generations after Fra Angelico, were meticulously recorded in a whole variety of ways - in letters, memoirs, text books, commentaries on art - giving a vast body of evidence on which to draw. But in Fra Angelico's time no one wrote about art, so fleeting references in official documents, such as contracts or bills or the records of a monastery or church, have to be relied upon instead.

The first version of Fra Angelico's life was published in Giorgio Vasari's Lives of the Artists published in two editions in 1550 and 1568 – around a hundred years after the painter's death. Those who wish to believe Vasari's idealized account points out that he was on good terms with the monks of Florence's San Marco convent, where Fra Angelico spent many years and could draw on the stories told by the monks about their predecessor. But it is also known that the monks were prone to elaborate on the history of their order, to show it in the most favorable light.

Vasari describes Fra Angelico as a pious, simple, and unworldly man, by no means an intellectual and concerned only with his saintly devotion to religion: 'Fra Giovani Angelico ... was no less famous as a painter than as a devoted member of a religious order ... He could, if he wanted, have lived in the world in the greatest comfort and become rich through his art, for even as a young man he was already a master. But he chose instead, being pious by nature, to enter the Dominican order for his peace of mind and above all for the salvation of his soul ... Rightly indeed was he called "angelic" for he gave his whole life to God's service and to doing good works for mankind ... he was entirely free from guile and holy in every deed . . . . He kept himself unspotted from the world and, living in purity and holiness, was so much a friend of the poor that I think his soul is now in heaven.'

Fra Angelico:

This woodcut portrait of the artist, from Vasari's Lives, seems as serious and saintly as the haloed subjects of his paintings.

Title page of the 'Lives':

Vasari's work is the source of much of what 3 is known of Fra Angelico.

San Domenico, Fiesole:

This monastery, overlooking Florence, was Fra Angelico's base and houses several works.

AN ANGEL WITH A BRUSH

Vasari continues at length in this vein, adding that Fra Angelico would only work on sacred subjects and that tears would stream down his face as he painted a crucifixion. Thus Fra Angelico appears as a naive and saintly priest, very much a figure of the piously Catholic Middle Ages. He was actually named Fra Giovanni in orders, the 'Angelic' first appearing in documents written after his death although it probably did attach to him in later life. He has also come to Italy to be called 'Beato' - the Blessed. Although this beatification (technically the first step to official canonization) was made official only in 1984, it has for centuries colored his sentimental image.

There is some hard evidence for this view of the painter. He blossomed with many virtues', wrote Fra Domenico da Corella in about 1462. And in the 1480s, the unsentimental Manetti recorded that Fra Angelico received no money for his work - all the payments were received by the monastery - and that he never missed his religious duties in order to paint. But an alternative view can be gleaned from the art itself. This suggests a more dynamic and individualistic personality.

For Fra Angelico was a Renaissance rather than a medieval painter, one who put vigorously into practice the new discoveries about perspective, the effect of light and shade, about the importance of narrative unity in a single picture - about showing real people carrying out real actions in real places. His figures may be saints, but no less real for that.

The Dominican monastery which Fra Angelico entered as a young man, probably at about the same time as his brother Fra Benedetto, was at Fiesole - in the hills overlooking the great city of Florence. In the 15th century, it fell very much within the orbit of Florentine politics and ideas.

The Dominican order itself was fired by reforming zeal: its friars were dedicated to strict observance of monastic discipline and had a special duty to preach to the poor. At the time Fra Angelico joined, the leading influence was Giovanni Dominici, whose influential tract, Lucula Noctis, defended traditional spirituality against the encroaching materialist Humanism of the new Renaissance ideas. Fra Angelico must have been deeply involved in the debates between those like Dominici, who argued for simple faith in the mysteries of God's creation, and those who searched for rational explanations of the material world and man's place within it. Gradually over the years, the painter created a vivid and unique synthesis between the two currents, energetically drawing on Humanist discoveries to give force to the spiritual message in his art.

A monastery in the hills:

Fra Angelico entered the Fiesole monastery as a young man and, although he accepted commissions in Florence, other parts of Tuscany and Rome, it was his home for most of his life.

The Linaiuoli Altarpiece:

Among Fra Angelico's great works, this altarpiece was commissioned by the Guild of Linen Weavers of Florence in 1433. It was his first major commission and is his first dated work.

The Painter-Monks

Probably born within a decade of Fra Angelico, Fra Filippo Lippi (c. 1406-69) entered a monastery at an early age too. Unlike Angelico, however, he became a Carmelite - but was totally unsuited to religious life. Vasari, whose idealized word portrait of Fra Angelico resulted in that painter's unofficial beatification, pronounced of Lippi that 'his lust was so violent that when it took hold of him he could never concentrate on his work... When he was doing something for Cosimo de Medici in Cosimo's house, Cosimo had him locked in so that he wouldn't wander away and waste time. Lippi was renowned for his 'merry life'. A scandalous affair with a nun produced a son, the painter Filippino Lippi, and he was also tried for fraud.

A Self-portrait:

Filippo Lippi placed this image of himself in his great Coronation of the Virgin. It has traditionally been regarded as the artist's visual signature to a work of particular personal importance.

Madonna and Child:

This charming vision of the beautiful young mother, the chubby Christ Child, and the appealing angel is one of Lippi's bestknown and loved works.

THE SECULAR MONK

In the Fiesole monastery, he seems to have worked first on manuscript illuminations, but none have been definitely identified. A bill of 1429 shows the nuns of San Pietro Martire owed ten florins for a painting to the Fiesole Dominicans, presumably painted by Fra Angelico in the previous two or three years. Some scholars believe this is the much damaged San Pietro Martire triptych now in the San Marco museum. Its style suggests that Fra Angelico in the 1420s was under the influence of - and may even have been taught by - a painter - monk called Lorenzo Monaco. Other damaged and insecurely dated pictures by Fra Angelico from this period support this view. By 1432 he was obviously quite well known, at least among religious patrons, and produced an Annunciation, now lost, for the Servite order in Brescia, hundreds of miles north.

On 11 July 1433, Fra Angelico received a particularly important commission, this time from a secular source. This is significant because at the time in Florence secular institutions and individuals were gradually taking over much of the church's traditional dominance in the patronage of the arts, giving a major impetus to Renaissance ideas. Fra Angelico was to paint a Virgin and Child and Saints for the wealthy Linen Guild, The Linaiuoli Triptych. The architectural frame in the new classical style was to be designed by Lorenzo Ghiberti, a major Florentine sculptor. This contract must have made Fra Angelico more than ever aware of the new currents, and particularly of the revolutionary paintings of Masaccio who had died in his 20s a few years earlier. Under such influences, Fra Angelico grew out of his medieval style and produced his first Renaissance masterpiece.

Attempts to put the pictures of the next few years in order vex scholars and no two seem to agree. He produced a beautiful Annunciation for the church of San Domenico in Cortona, a Florentine-dependent city to the south. Then, probably in 1434, there was a magnificent Coronation of the Virgin painted for his own Fiesole monastery. For the church of Santa Trinità in Florence, he painted The Deposition from the Cross. These works show he had by now a team of assistants to enable him to work on a large scale while still maintaining his highly finished and detailed technique.

In 1436, the Dominicans took over the monastery of San Marco in Florence, and at the bidding of Florence's Medici rulers began remodeling it in 1437. Soon after this, Fra Angelico began one of his greatest achievements, the series of frescoes that still adorn the monastery today. Over a period of years - probably 1440 to 1445-he decorated dozens of rooms. Fra Angelico could not have carried out such a huge body of work alone and some scholars claim that only a small proportion is entirely by his hand.

St Antonino:

The subject of this portrait was the prior of San Marco in Florence. It was he who engaged the monk to decorate the cells, cloister, and great hall. So great was the prior's simplicity of life and pastoral zeal that he was regarded as a saint and miracle worker during his lifetime.

Monastic solitude:

In 1436, the monastery of San Marco, Florence, was taken over by the Dominicans, and Fra Angelico was given the responsibility of its decoration. Most of the frescoes are in the otherwise bare cells of the monks, and were intended to aid contemplation.

The cloisters of San Marco:

Along the upper walls of this serene courtyard can be seen the beautiful frescoes executed in the 1440s. The cloister subjects include saintly monks - St Thomas Aquinas and St Peter Martyr - and Christ was received as a pilgrim by two Dominicans. These paintings were designed to act both as exaltations of the religious life and as inspiration for the inhabitants.

However, the bulk of the work shows that he maintained tight control over the design and execution of the pictures and the most important, larger scenes are unmistakeably his work. As befits their setting and devotional purpose as inspiration for meditation, most of the frescoes are extremely simple, showing New Testament scenes or incidents from the lives of the saints and martyrs in plain landscapes. Few visitors to the monastery in Florence today can fail to be moved by these poignant expressions of the religious way of life in their original setting.

Fra Angelico's fame had by now spread far beyond the Dominican order and the cities of Tuscany, and in about 1445 he was summoned to Rome by Pope Eugenius IV. He seems to have gone there in 1446 and to have painted some frescoes, now lost, in the Capella del Sacramento of St Peter's. In 1447 Eugenius was succeeded by Nicholas V, the first true Renaissance pope, who commissioned from Fra Angelico some fresco decorations for his study and private chapel. The latter survives, decorated with scenes from the lives of St Stephen and St Lawrence. These are among Fra Angelico's finest works, combining naturalism and spiritual gravity with the ful solemn power of the Renaissance idiom. In 1447 the pope allowed Fra Angelico to leave Rome to escape the unhealthy summer heat and he went to Orvieto, where he worked with collaborators, including his outstanding pupil Benozzo Gozzoli, decorating the vault of the Capella della Madonna di San Brizio in the cathedral.

A papal commission:

The small private chapel of Nicholas V is decorated with frescoes of exceptional clarity, depicting the lives of Sts Lawrence and Stephen, two of the martyrs of the early Church.

THE PATRON POPE

The relationship with Pope Nicholas V was clearly of some importance, for the pope was thoroughly imbued with Humanist ideals and embarked on major building and artistic projects in Rome which provided a powerful stimulus to Renaissance art. The pope seems to have admired Fra Angelico greatly and according to Vasari offered him the post of Archbishop of Florence when it fell vacant. Vasari tells the story to show how the modest and simple monk turned it down, encouraging! pope instead to appoint another Floren Dominican in his place. But Fra Angelico has been more worldly than Vasari allows, to have been offered a position with important political connotations. In 1450, Fra Angelico returned to his home monastery of Fiesole. But in 1452 his term as prior there came to an end, and he returned to Rome to paint another chapel for the pope in about 1453. Two years later, on 18 February 1455, Fra Angelico died in Rome, in the monastery of Santa Maria Sopra Minerva. He was buried in the monastery church under a simple effigy of the artist in his monk's habit.

Orvieto Cathedral:

Two frescoes span the vault of the chapel of the Madonna di San Brizio, both begun by Fra Angelico in 1447. They formed the basis of an unfinished grander scheme, the Last Judgement.

Tomb of Fra Angelico:

Fra Angelico died far from the hills of his native Tuscany. The lines of the Humanist poet Lorenzo Valla, carved under the feet of the artist, declare: 'Let me not be praised as another Apelles, but because I gave my riches O Christ to Thy people; For the deeds that count on earth are different from those in heaven.'

Angelico's Brilliant Pupil

Fra Angelico had a large workshop, but the only one of his pupils to attain distinction as an independent artist was Benozzo Gozzoli (c.1421-97). Although he painted religious subjects, his outlook was secular. He was an excellent draughtsman and loved detailing the glittering trappings of horses and courtiers. But he was not simply a 'pretty' painter; his command of foreshortening and perspective was great, and many of his characters were drawn from life. Thus, his work contains much of interest to the social as well as the art historian. His greatest work was The Journey of the Magi, which in its splendor and richness reflects his original training as a goldsmith. There is also a series of frescoes in the Campo Santo in Pisa and an altarpiece in the National Gallery, London.

The Journey of the Magi:

Many of the faces in this panorama belonged to the members of the great Medici family and their court. The fresco was commissioned in 1459 to decorate the private chapel of the Medici palace. It is an unashamed tribute to the wealth and conspicuous consumption of the Medici family.

A proud self-portrait:

Almost lost among the myriad faces in the great cavalcade of the Magi, below, is the proud, inscrutable face of the painter, with the words declaring his authorship of the work embroidered on his cap.

THE ARTIST AT WORK

The Work of an Angel

It is tempting to attribute the stunning beauty of Fra Angelico's work to divine inspiration, but that would be largely to disregard his abilities and self-discipline as a highly skilled artist.

The great Victorian art critic John Ruskin summed up the traditional view of Fra Angelico when he wrote that he was 'not an artist properly so-called but an inspired saint. Fra Angelico was certainly pious, but Ruskin was totally misleading in suggesting that he was anything other than a highly professional artist. He was not only in the vanguard of ideas but also ran an efficient workshop and traveled considerable distances (to Rome and Orvieto) to take up commissions. There were several other painter-monks who achieved great distinction during the Renaissance - his contemporaries Lorenzo Monaco and Filippo Lippi, and two generations later Fra Bartolommeo, who worked at Fra Angelico's monastery of San Marco. None of them, however, has matched the popular appeal of Fra Angelico, whose great achievement was in combining the highest technical skills with a sense of radiant spirituality.

Certain features of Angelico's style show through virtually all his work, especially his decorative sense and wonderful skill with color, but his art developed greatly during his career, which falls into three broad phases. In the first, he appears as an artist of tremendous innate talent, but still working largely within traditional conventions. In the second phase, his work takes on a greater clarity and weight as he absorbs and refines the ideas of his great contemporaries. And in the third, he excels as a fresco decorator.

Scenes from the life of St Nicholas:

Here St Nicholas is addressing an imperial messenger and saving a ship at sea. This is one of the three predella panels of a polyptych (several panels hinged together) painted by Fra Angelico for the chapel of St Nicholas in the church of San Domenico, Perugia.

'Sacra Conversazione':

The San Marco Altarpiece, 1438-40, commissioned by Cosimo de Medici. This is one of the first 'sacred conversations' in which Fra Angelico abandoned the polyptych and showed the Madonna, angels, and saints in a unified area. Many devices have been used to give the illusion of space – the receding patterns on the carpet, the trees beyond the walls, and the looped curtains enclosing the foreground.

Wall painting:

Fresco's painting began with a sinopia - a drawing on a wall that was used as a guide. Each day a different section was covered with wet plaster and then painted. The plaster and paint dried together, giving a highly permanent surface. Restoration work at San Domenico, Fiesole, has uncovered some of Fra Angelico's sinopia so that drawing and fresco can now be compared.

JEWEL-LIKE WORKS

Angelico's earliest works, small and jewel-like, are the sort of paintings for which the initial commissioning contract would specify the amount of gold or expensive blue pigment the painter was required to use. They were intended to decorate the altars of chapels at Fiesole and in other Dominican establishments. Fra Angelico was also involved in work on manuscript illumination at this time, an activity much favored as a part of the devotional observance of a young friar. The gorgeous Cortona Annunciation marks the culmination of this early phase but also - in the insistent perspective of the architecture - looks forward to his more naturalistic later style.

A key work in his development is the Linaiuoli Altarpiece, the celebrated work produced for the Florentine Linen Guild in 1433. The magnificent frame is by Lorenzo Ghiberti, the most famous sculptor of the day, and it pulls together the various panel's Fra Angelico painted and makes them into a coherent whole. When the altarpiece's doors are shut, two solid, monumental saints (Mark and Peter) stand next to each other on a firm platform of rocky ground. When they are open, Saints John the Baptist and John the Evangelist flank the Virgin and Child, witnesses and guards. Beneath them all, three small panels, known as the 'predella', contain self-contained scenes showing St Peter Preaching, The Adoration of the Magi, and The Martyrdom of St John the Evangelist. Each is a superbly imaginative interpretation of how the real events may have looked. Only the angels decorating the painted arch framing the Virgin and Child panel seem to belong to the earlier, more archaic phase of the painter's work.

Virgin and Child with Saints Dominic, John the Baptist, Peter Martyr, and Thomas Aquinas:

This is the earliest painting by Fra Angelico which can be given a positive date. It was installed in 1429 on the high altar of the church of San Pietro Martire, Florence, and was probably completed in the previous year.

THE RENAISSANCE INFLUENCE

Fra Angelico did not stumble on this Renaissance clarity overnight. His earlier works all show some influence of Renaissance ideas - unified lighting, naturalistic plants and other details, real weight to the fall of the draperies of the saints' clothing, and, most significantly, scientific use of geometric perspective to create an illusion of depth in the picture. But in the Linaiuoli Altarpiece, and other works of the 1430s such as The Deposition from the Cross painted for Santa Trinità in Florence, they become his guiding principles.

For all the beauty and splendor of his panel paintings, it is on his frescoes that Fra Angelico's fame and popularity mainly rest. The art of fresco painting was more highly developed in Italy than in any other country and for centuries was regarded as the only fitting outlet for an artist's grandest thoughts. Italy's bright light means that churches there (compared with those in northern Europe) tend to have small windows and consequently large areas of walls that can be covered with paintings. And Italy's generally dry climate is ideal for preserving frescoes, which can deteriorate rapidly if the walls on which they are painted become damp.

The sheer scale of the demands placed on Fra Angelico required him to work with a considerable team for his fresco cycles. First, the wall would have to be carefully plastered, ready to take the master's design. Over this, a top layer of fine wet plaster was applied, just enough to be painted in one day, The work would then have to be quick and accurate in order to be completed before the plaster dried and could no longer take up the paint. Remarkably, a few of Fra Angelico's own underdrawings or sinopia have been uncovered during the restoration of his frescoes in San Marco and at Fiesole. With the top layer of painted plaster removed and mounted on a new base, we can see the extraordinary drawings that lay beneath.

This was the clarity of vision that enabled him. to carry out large and complex schemes with numerous assistants, yet still ensure that the works were his own. When he went to Rome to work for Pope Nicholas V he took a whole team of assistants, the most important being Benozzo Gozzoli, but stamped his own artistic personality on the work.

Fra Angelico lived at a time when the role of art was changing to something to be appreciated for itself rather than solely for its religious meaning or decorative function. His work showed that the human messages of the Renaissance could be charged with the fervor of Catholic Christianity. Indeed, he succeeded like no other painter of the Renaissance, or any other period, in creating a synthesis between piety and grandeur.

COMPARISONS

Paintings of the Annunciation

The Annunciation is the announcement by the angel Gabriel to the Virgin Mary that she has been chosen by God to become the mother of Christ. It became a popular subject in painting during the 14th century and built up a rich tradition of symbolic detail. Gabriel usually holds a lily to denote her purity, but in Sienese paintings (like works by Simone Martini) he holds an olive branch. The lily was the civic emblem of Florence, and Siena had a long-lasting feud with that city. Other artists, like Poussin, in the 17th century, showed the Holy Spirit descending towards Mary in the form of a dove, and treated the subject matter as a 'normal' event using natural emotions and gestures.

Simone Martini (c. 1284-1344) The Annunciation:

With exquisite craftsmanship, Simone shows Mary recoiling in surprise from the angel Gabriel.

Nicolas Poussin (1593/4-1665) The Annunciation:

In this serene painting, Mary receives the angel with outstretched arms and sits crosslegged on the ground.

THE MAKING OF A MASTERPIECE

The Deposition

The Deposition (see pages 784 and 785) was painted on a single panel for the Strozzi chapel in the church of Santa Trinità, Florence. It seems that the artist Lorenzo Monaco painted the three pinnacles of the altarpiece before his death in 1425. It was then probably left unfinished and Fra Angelico worked on it at a later date, completing it around 1443. The body of Christ is lowered from the cross in the centre, the two ladders resting on the cross emphasizing the vertical design, and the kneeling figure in the foreground leads the spectator's eyes to the central group. The standing figures on either side of the work help to enclose it, aided by the tower of a building on the left and a tree on the right. The inscription under the right panel reads Ecce quomodo moritur iustus et nemo percipit corde' (See how a just man dies and no one feels it in his heart). The painting is full of superbly observed details, but they do not detract from the tragic grandeur of the scene.

Ideal landscape:

Fra Angelico was a remarkable landscape painter as is shown in this background of a Florentine town and serene Tuscan countryside taken from the left panel of The Deposition. Note the greybrown hills which recede into the distance, the horizontal lines of clouds, and the solid walls of the town which seem to glow in the light of the setting sun.

Citizens of Florence:

This group of men from the right side of the Deposition is all in contemporary Florentine dress, contrasting with the biblical robed figures on the left side. One of the men holds the nails and the crown of thorns taken from the body of Christ, underlining the physical pain of the crucifixion.

Preliminary work:

The Lamentation over the Dead Christ was commissioned for the oratory of Santa Maria della Croce al Tempio in April 1436 and was completed in December. This work is almost like a preliminary design for the later Deposition. The foreground is filled with figures in private grief; the background is a strange and remote landscape.

Gallery

Fra Angelico's works reflect the serenity, discipline, and anonymity of the communal religious life. But he still managed to infuse them with compassion which is what gives them their timeless appeal. Each time he painted an already familiar theme, he was still able to give it new expression and development-compare the early Cortona Annunciation with the San Marco version, painted 20 years later. The Deposition from the Cross is another good example of a formal religious composition filled with deep emotion and humanity.

The frescoes of San Marco-Noli Me Tangere and The Coronation of the Virgin - dominate the convent cells. They were aids to meditation and spiritual exercise and were simple, constant reminders to the friars of the religious discipline necessary to the community. The restrained economy of these frescoes contrasts well with Scenes from the Life of St Lawrence which emphasize the narrative and include a wealth of extra details. The Flight into Egypt and the Massacre of the Innocents develop this realism even more intensely and take Fra Angelico firmly into the main body of 15thcentury Italian painting.

The Annunciation c. 1433-34:

This is the first undoubted masterpiece painted by Fra Angelico, which his followers then tried to imitate. Beneath an arcade partly enclosed by columns, the Virgin leans forward to hear the angel's message while, to the left, Adam and Eve are being expelled from the Garden of Eden. There is a strong sense of mystery and earnestness.

Noli Me Tangere c. 1441-45:

One of a series of Scenes from the Life of Christ, which decorate the 11 cells on the upper floor of the San Marco monastery. This fresco is in Cell 1. The two heads are both carefully silhouetted against different backgrounds; note the minutely observed foreground.

St Lawrence receiving the Treasures of the Church c.1447-49:

This work is part of a fresco cycle commissioned by Pope Nicholas V and is the only surviving series painted in Rome by Fra Angelico. It shows Pope Sixtus II giving St Lawrence the church treasures while Roman soldiers beat down the door.

IN THE BACKGROUND

Monastic Life

By the 15th century, the monasteries had become notorious for their worldliness and debauchery, yet there were some devout orders in which monks led austere lives of study and prayer.

"They cheat, steal, fornicate, and when they are at the end of their resources they set up as saints and work miracles.' Such was the charge made against friars by the 15th-century Italian author Masuccio, and his opinion was shared by many of his contemporaries.

In the growing secular and commercial atmosphere of Renaissance Florence, monastic life appeared parasitic. The most virulent dislike was reserved for the friars in the mendicant (begging) orders - the Franciscans, Dominicans, and Carmelites, all of whom had settled in Florence during the 13th century.

But to a large extent, it was the hypocritical flouting of the basic monastic rules of poverty, chastity, and obedience which inflamed the public. Contemporary records make it clear that it was not unusual for friars and priests to carry weapons and hunt, or to keep mistresses and father children.

Obedience to religious rules seemed equally lax in many convents of nuns. Masuccio went so far as to claim: 'Some nuns are formally wedded to monks, with the accompaniments of mass, a had become notorious for there were some devout orders lives of study and prayer.

marriage contract and a liberal indulgence in food and wine. The nuns afterward bring forth pretty little monks or else use means to hinder that result'.

No doubt exaggerated for satirical effect, Masuccio's claim nevertheless held more than a grain of truth. Often, monasteries and nunneries were close enough for members of the orders to mingle - and share beds. Monastery archives testify to this fact with their volumes given over to the trials of cohabiting monks and nuns. Immorality was so rife that rumours began to be heard in favour of priests marrying.

In addition to this, the religious orders were openly becoming more worldly. They courted the patronage of princes and businessmen, owned large amounts of land, sold pardons and deathbed absolutions, and concerned themselves intimately with the affairs of the people and political life. Some monks also took advantage of the anonymity and sanctity their habits afforded them and acted as agents and go-betweens in conspiracies and murder plots.

Dens of iniquity:

Accusations that the monasteries were dens of avarice, impiety, fornication, and sodomy were widespread from the 13th century onwards. This fresco shows a scene from the life of St Benedict, who rejected the dissolute lifestyle of the monasteries and their prostitutes to pursue a solitary life of prayer.

Santa Maria Novella:

The church of Sta Maria Novella became the Florentine home of the Dominicans in 1221, just a few years after their arrival in the city. Together with the Franciscans, they led the great religious revival of the 13th century, preaching obedience to the Roman Papacy.

The jolly friar:

The easy life in many monasteries gave rise to the popular image of the jolly friar. In reality, he was far from typical, particularly in the Mendicant orders of Florence, where life was austere and monks followed a rigorous discipline of prayer, work, and study.

The devil in the pope's robes:

Disillusionment and dissatisfaction with the church was a popular subject in literature and art. This 15th-century miniature shows the pope with a demon's claws, handing out the fruits of temptation to the bevy of ladies surrounding him.

POOR CANDIDATES

A decline in monastic standards was almost inevitable at a time when candidates were admitted too easily and for the wrong reasons. Many were the children of impoverished noble families who paid a one-off sum to the monastery to secure a respectable career for their offspring, and not all had true vocations for the religious life.

The level of learning was generally not high and many candidates had no aptitude for study. However, there were those who pursued lives of prayer, study and work, and monks who belonged to the well-endowed monasteries in the great city-states of Pisa, Milan and particularly Florence were the privileged members of some of the best centres of learning in Europe.

Nowhere are the extremes of monastic types more apparent than in the lives of the Florentine painter-monks, Fra Angelico and Fra Filippo Lippi. In 1421 Lippi, an orphan was placed in the Carmelite priory in Florence.

But his unsuitability for such a life was shown by his subsequent trial for fraud, and his abduction of a nun, Lucrezia, whom he later married and who bore him a son, Filippino, who also became a painter.

In marked contrast, Fra Angelico led a reverent life within the Dominican order, earning for himself the title of Beato, meaning 'blessed one'. Although the qualities of spirituality and grace that are found in his paintings may have enhanced his reputation, his life in the Florentine monastery of San Marco was certainly a devout one.

Carmelite priory in Florence. But his unsuitability for such a life was shown by his subsequent trial for fraud, and his abduction of a nun, Lucrezia, whom he later married and who bore him a son, Filippino, who also became a painter.

In marked contrast, Fra Angelico led a reverent life within the Dominican order, earning for himself the title of Beato, meaning 'blessed one'. Although the qualities of spirituality and grace that are found in his paintings may have enhanced his reputation, his life in the Florentine monastery of San Marco was certainly a devout one.

The Mendicant friars :

The Mendicant orders brought religion to the urban poor. they supported their activities by begging, which made them very unpopular in the growing commercial atmosphere of 15th century Florence.

THE DOMINICANS

From the early 13th century, the Dominican order had been based in the western part of Florence, around the church of Sta Maria Novella. The Dominicans stressed religious orthodoxy and obedience to the pope. They had a strong commitment to learning as well as to preaching and set up studio general, a form of higher education catering not only to members of their š own order but to secular students too. Similar establishments were founded by the Franciscans i and Augustinians in other parts of the city. The teachers came from within the order but were sent to study abroad at universities such as Paris and Bologna. Dante, a pupil of the studies, is proof of the high standards of learning that the system fostered.

The history of the Dominican monastery of San Marco demonstrates the close links between political and business interests and religious life. Although professing humanist ideas, Cosimo de Medici - the ruler of Florence - was anxious to keep his Christian life blameless. Apparently suffering from prickings of conscience that 'certain portions of his wealth had not been righteously gained', Cosimo was advised by the pope to use the money to extend the monastery around the church of San Marco, which he had recently handed over to the Observantist Dominicans, a reforming branch of the order. In this way, Cosimo could 'unburden his soul'.

Work began on the new monastery and library of San Marco in 1437. The plan followed traditional monastic lines, with the rooms built around three sides of a cloister, with the guest hospice, the chapter house and the refectory downstairs, and the monks' study cells, dormitories, and the library on the first floor. But the light, classical simplicity of the architecture set the monastery apart from others in the city, and the library became a pattern for subsequent Italian monasteries. When in 1444 Cosimo donated a collection of over 400 Greek and Latin manuscripts to the library, San Marco became the largest and most influential of the early public libraries in Italy.

The second prior of San Marco was Antoninus Pierozzi, who took up his post in 1439 and later authorized the decoration of the monastery's cell walls with the wonderful frescoes of Fra Angelico. He later became Archbishop of Florence and was made a saint at his death. His life was led according to the austerest Dominican precepts; he gave a third of his income to charity and, as was the monastic rule, provided food and sustenance to the Florentine poor and the swarms of beggars who visited the monastery with their children. He also founded an organization for the poveri vergognosi, the 'embarassed poor', who were too ashamed to let their poverty be known publicly.

Antonino's moral guidance also led to a drive to reform both the Florentine clergy and monastic discipline within his own monastery. Here the principles laid down for all Dominican friars were strictly observed, with the celebration of the six liturgical offices, each lasting for three hours, forming the basis of the monastic day.

In most orders, there was little privacy, with monks sleeping in large dormitories. Because of the Dominican emphasis on learning, individual cells had developed, where members could obtain a degree of privacy and silence for studying. These were generally small rooms arranged on each side of a central corridor, from which the interior of each cell as visible.

San Marco Library:

The building of the library at the Dominican monastery of San Marco was part of the extensive renovations carried out with money donated by Cosimo de Medici. With his help, it became one of the largest and most respected libraries in Renaissance Italy.

Simple fare:

St Benedict and his sister St Scholastica share a simple meal of fish, bread, and wine. Meals in most monasteries followed a similar pattern of frugality - meat was not permitted.

Italy's greatest poet:

Dante Alighieri (1265-1321) was the most outstanding product of the Florentine religious schools, where he studied for two-and-a-half years. His most famous work, The Divine Comedy, is an allegorical poem that illustrates the tragedy of the human condition and shows the way to happiness through the Christian faith.

MEALS AND RECREATION

Meals were frugal, although the Florentine orders were well provided by their farmlands in Tuscany, which supplied them with wine, wheat, beer, and oil. Two meals a day were eaten in summer (from Easter to mid-September) and generally only one in winter. Extra food was allowed on feast days but no meat was served in the monastery. Wine or beer was commonly served at meals, although it was frequently withdrawn as a penance. The silence was observed at meals and for most of the day.

After the midday meal came a brief period of recreation when friars could talk or exercise on the gardens. Relaxation did not include running, playing games, laughing loudly or singing - especially singing vulgar songs - although, by the Renaissance, many warnings for this kind of behaviour are recorded.

The Franciscans:

The followers of St Francis of Assisi settled in Florence at the beginning of the 13th century, establishing themselves in the small church of Sta Croce, which developed into an impressive monastery. A Mendicant order based on the precepts of poverty and humility, it had lost much of its popularity by the 15th century.

DECLINING STANDARDS

After the death of Antonino, the standards at San Marco declined until later in the century when the puritanical zeal of a yet more famous martyr Savonarola, brought a new wave not only within the walls of the mona but throughout the whole of Florence.

Savonarola's study cell:

It was here, in a study cell at San Marco, that the Dominican reformer Savonarola wrote many of his sermons and devotional and moral essays. He was made prior of the monastery in 1491 and re-established the discipline of the order, relegating many of the less diligent scholars to a retreat located outside Florence.

William Blake ‘The Painter Poet’

-

Posted by

Umaid

- 0 comments

Warli Painting

-

Posted by

Umaid

- 0 comments

Titian ‘The Italian Renaissance’

-

Posted by

Umaid

- 0 comments

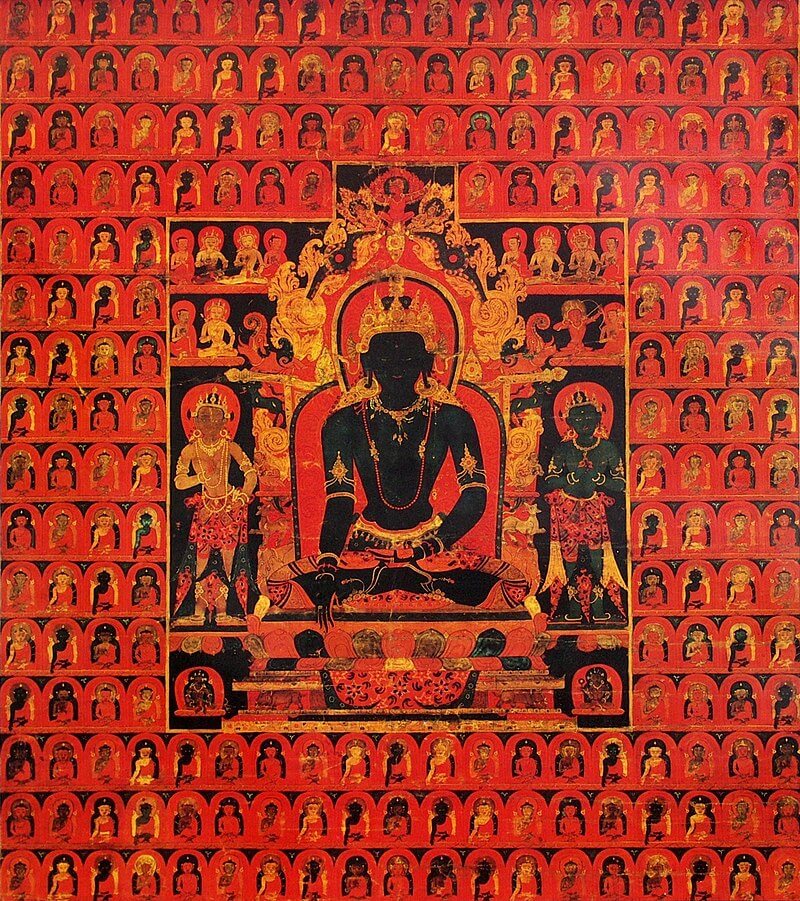

Thangka Painting Style

-

Posted by

Umaid

- 0 comments

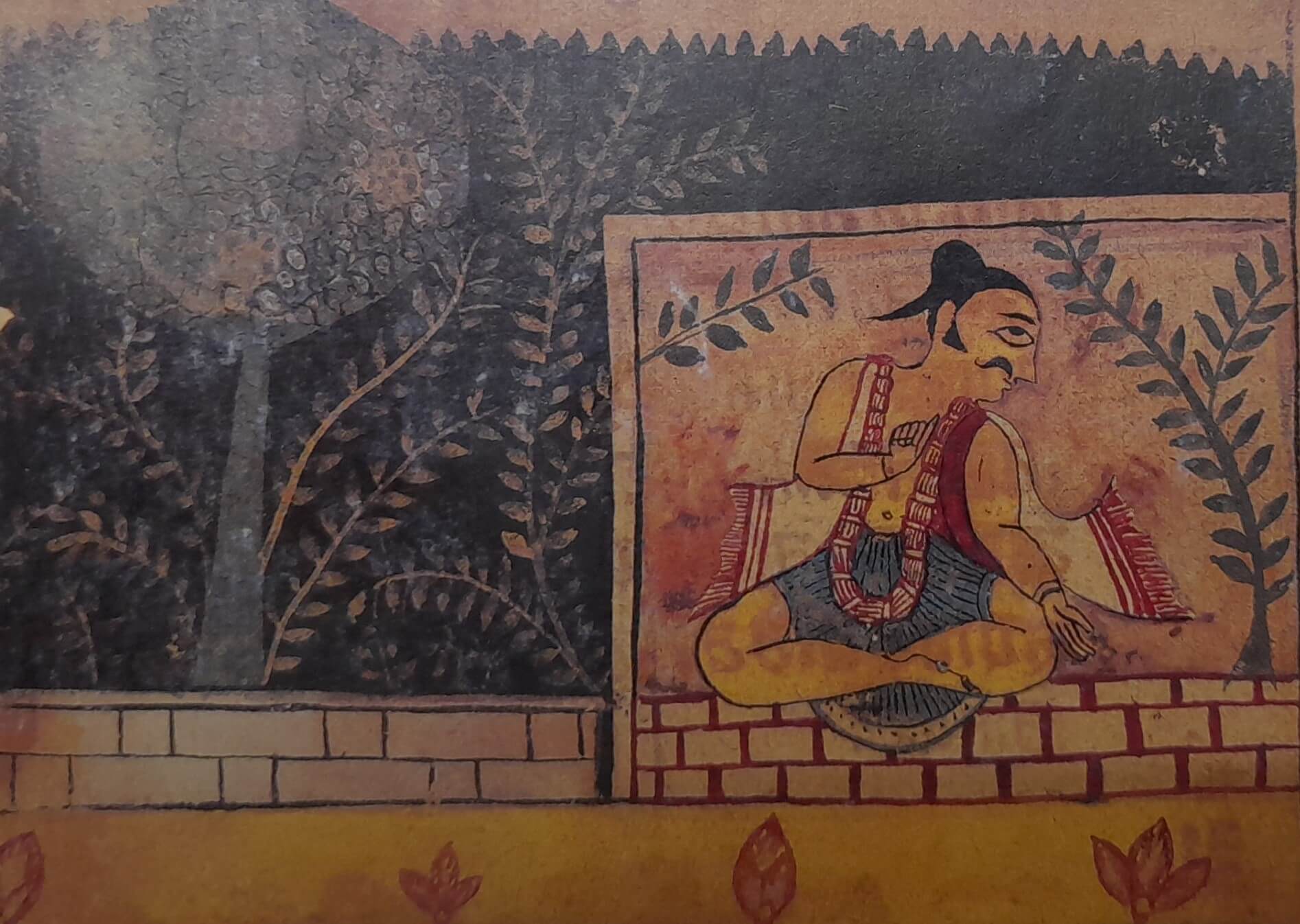

Pre- Mughal Traditions of Painting in Marwar

-

Posted by

Umaid

- 0 comments

Pieter Bruegel the Elder ‘The Draughtsman and engraver ‘

-

Posted by

Umaid

- 0 comments

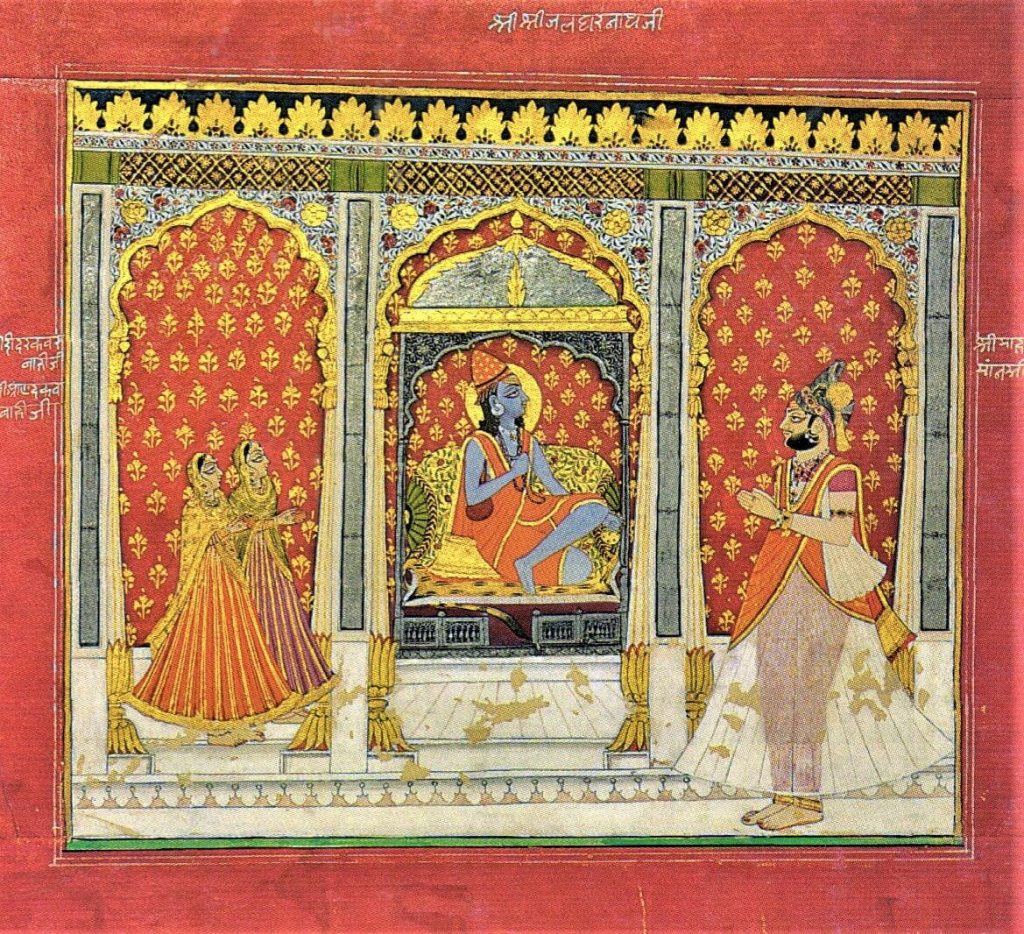

Pichwai Paintings of Rajasthan

-

Posted by

Umaid

- 0 comments

Phad Paintings of Rajasthan

-

Posted by

Umaid

- 0 comments

Paul Gauguin ‘Mysteries of Paradise’

-

Posted by

Umaid

- 0 comments